Friday, October 10, 2008

The Uninvited (1944)

Considering the sheer number of horror films to come out of Hollywood during the 1940’s, it is simply astonishing that there should be so few movies about hauntings made during that decade in which the ghosts turn out to be unambiguously real. In fact, I’m pretty sure Paramount’s The Uninvited (helmed by Lewis Allen, who would become an enormously prolific television director in the mid-1950’s) is the only one I’ve ever seen. Whereas most 40’s “ghost” movies portrayed phantoms, wraiths, and specters who would eventually stand revealed as a Nazi spy or the impossibly wealthy young heroine’s avaricious uncle or some such thing, The Uninvited plays it completely straight, and even goes so far as to posit a house haunted by two ghosts— one of them good, the other evil, and the both of them squabbling fiercely over the fate of someone still living. Nor is it, as was generally the case on those extremely rare occasions when a 40’s film dealt with an authentic ghost, a comedy or a romance. There are elements of both comedy and romance in The Uninvited, but the movie’s main business is unquestionably the protagonists’ quest to uncover the secrets that will finally lay the warring spirits to rest.

Those protagonists are pianist and London newspaper music critic Roderick Fitzgerald (Ray Milland, from Terror in the Wax Museum and The Premature Burial) and his sister, Pamela (Ruth Hussey). The Fitzgeralds are nearing the end of a holiday in Cornwall when they discover a huge and beautiful mansion standing abandoned atop the sea cliffs overlooking the Atlantic. The pair end up letting themselves in through an open window when their dog, Bobby, chases a squirrel inside, and Pamela instantly falls in love with the place. It reminds her very much of the house where she and Rick grew up, and it’s in such an excellent state of preservation that it would not be utterly ridiculous to imagine living there. Pam talks her brother into checking around to discover who owns the place, and making an offer to buy in the event that the house on the cliff is for sale.

The house turns out to belong to a retired naval officer by the name of Commander Beech (Donald Crisp, from Svengali and the 1941 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). When the Fitzgeralds go to see Beech, they are greeted by his granddaughter, Stella Meredith (The Unseen’s Gail Russell), who tells them that the commander is out at the moment, but should be returning relatively soon. While Pam and Rick wait in Beech’s study, they mention to Stella that they’re interested in buying the old mansion, which the girl identifies as Winward House. This obviously disturbs Stella for some reason, and she begins attempting to hurry the visitors out, saying that Winward House is not for sale, regardless of what Roderick may have heard to the contrary. That’s when Beech comes home. In flat contradiction to what his granddaughter was saying, Beech confirms that he is looking to sell Winward House, and indeed that he’s willing to do so for even as little as £1200, the almost insultingly low figure which Rick offers (presumably in an attempt to indulge his sister’s new fixation while simultaneously stacking the deck against actually having to follow through on it). The Fitzgeralds are stunned, and though Roderick makes a short-lived effort to backpedal, Pamela pushes him ahead into closing the deal.

So why was Commander Beech so eager to unload the mansion on the cliff, and why was his daughter willing to resort to subterfuge to stop him from doing so? Well, the house had been in Beech’s family for generations, but its last occupants were his daughter, Mary, and her husband, a painter named John Meredith. Stella also spent the first years of her life under its roof. Mary was killed in a fall from the cliffs when Stella was three years old, and Meredith died too not long thereafter. The house thus has strong associations for both the old man and his granddaughter, but their respective currents of sentiment run in opposite directions. For Stella, Winward House is all that remains of her mother; for Beech, it is the scene of the most terrible loss he has ever suffered. As we shall see, however, there is more to the commander’s desire to be quit of Winward House than painful memories. Ever since Mary Meredith died, the mansion has had a reputation for hauntedness, and though Beech is at pains to deny any such thing, he does indeed believe that there are spirits walking its corridors. More to the point, he believes that there are malign spirits, which mean to do harm to Stella specifically.

A rather large monkey wrench is thrown into Beech’s plan for keeping his granddaughter and the ghosts at arm’s reach from each other, however, when Stella befriends the Fitzgeralds shortly after they move in, and indeed strikes up a romance with Roderick. The commander forbids the relationship, but he finds a modern-minded twenty-year-old girl to be rather less controllable than the crew of a torpedo boat destroyer, and all he really accomplishes is to make himself sick with emotional overexertion. So concerned does he become, in fact, and so resistant does he find Stella, that he places a phone call to a mysterious woman named Holloway (Cornelia Otis Skinner) to make arrangements for the girl’s removal from the scene by force, should no other option present itself. Meanwhile, the Fitzgeralds are discovering that the rumors of “disturbances” in Winward House are absolutely true. The pets refuse to set foot on the second floor, cold drafts blow through the house in places where they can’t be accounted for, a woman can be heard sobbing shortly before dawn nearly every morning, maid Lizzy Flynn (Barbara Everest, of Gaslight and These Are the Damned) sees a spectral apparition of a woman in white, and the room upstairs which John Meredith used as his studio gives off an inexplicable aura of menace and despair. Nor does it take long before Stella encounters the strange manifestations at Winward House, but she reacts to them rather differently than the place’s new owners. Though she is initially as frightened as anyone by the presence in the studio, and though something briefly seizes control of her and causes her to come within an ace of running off the cliff to her almost certain death, there is something else in the house which Stella finds soothing and comforting. In particular, there is something in Winward House which manifests itself with the smell of mimosas, and it is that scent that convinces Stella the mansion is haunted by her mother. You see, when she was but a child, her father gave her a bottle of her mother’s perfume, which she has since parceled out so sparingly that she still has a small quantity of it even today; that perfume smells strongly of mimosa.

All of this gives Pam and Rick a great deal to think about. On the one hand, they know very well that strange and inexplicable things routinely occur in their new house, but Roderick at least is not quite ready to dive headlong into believing the place is haunted. Stella, unshakably convinced that it’s the spirit of her mother in Winward House, wants to spend as much time there as possible, but her first encounter with the forces inhabiting the place nearly killed her. After talking the matter over with neighborhood physician Dr. Scott (Alan Napier, from Journey to the Center of the Earth and Isle of the Dead), Roderick and Pamela decide to stage a séance in Winward House. Neither of the men believe in the efficacy of such things, but they think Stella will, and they also believe there’s a good chance that a fake message from Mary Meredith directing Stella to steer clear of the house will keep her safe from whatever it is that nearly pitched her off the cliff that night. The séance initially goes perfectly according to plan, with the improvised ouija board identifying the ghost as Stella’s mother, and denying that it wants Stella in the house with it, but then things diverge rather sharply from the script. The makeshift planchette suddenly begins picking up real signals from the ghost, which informs Stella that it is in the house not because it was waiting around for a reunion, but because it is standing guard. If the ghost is to be believed, there is a second presence in the house, somebody named Carmel, and that this second presence is a danger to Stella. Then the room grows cold, and something seizes the wineglass which Stella, Scott, and the Fitzgeralds had been using as their planchette, and shatters it against the nearest fireplace.

So who is this Carmel, and what does she have to do with Winward House and the Meredith family? As Rick and Pamela will gradually piece together, Carmel was an artist’s model whom Stella’s father often employed, and with whom he was cheating on his wife. She was at Winward House on the night when Mary Meredith died, and her presence has led to much speculation over the possibility that Mary’s fall was neither accident nor suicide, but murder instead. But whatever happened between the two women out on the cliffs, it went nearly as badly for Carmel, who died herself just a couple of days later. Furthermore, Dr. Scott has in his possession a diary kept by his predecessor which makes it sound as though Carmel may have been allowed to die deliberately by the nurse who treated her in the aftermath of the confrontation. That nurse had been hired by the family to look after Commander Beech, who had a weak heart even back then, and there is some indication that she was Mary Meredith’s lesbian lover as well— certainly that would go some way toward explaining why Mary put up with her husband’s infidelity for so long, to say nothing of the motive it would provide the nurse for a revenge killing after Mary’s fatal fall. The nurse’s name? Why, it’s Holloway, of course. But as is usual for movies like this one, the ties between Carmel and the Meredith family were really much more complicated than is realized by anyone who is willing to talk about them, and Stella herself is at the center of the undying rivalry between the two dead women.

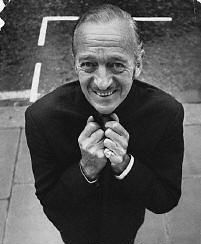

So far as I’ve seen, nobody but RKO was making horror movies as serious and mature as The Uninvited as a matter of course during the 1940’s, and to watch The Uninvited is to wonder why the hell not. Though it is hampered by a few descents into the maudlin or the saccharine, and by an obtrusively melodramatic score from the unaccountably well-regarded Victor Young, The Uninvited was probably the best cinematic ghost story to be made in the English-speaking world until Robert Wise’s The Haunting almost twenty years later. The spook scenes are commendably creepy— even the ones involving the benevolent ghost of Stella’s mother— and the visible manifestations of the evil ghost are nearly as effective as the nightmare scene with the animate wedding dress in The Amazing Mr. X. The mystery surrounding the haunting is unraveled in a believable manner, and the answers that are uncovered involve a startling amount of taboo material for a 1940’s Hollywood film. What levity there is comes not in the form of typical comic relief, but rather through the much more satisfying expedient of making one of the central characters a roguishly sarcastic wise-ass. And speaking of that roguishly sarcastic wise-ass, B-movie fans are likely to be knocked for a loop by Ray Milland’s performance. We, after all, are accustomed to seeing him as an older and grouchier man in the movies he made for American International during the 60’s and 70’s; his turn here as a dapper young sophisticate— let alone a romantic leading man— sets him in an entirely new context, and one which he inhabits with unexpected ease and assuredness. All in all, the biggest mystery in The Uninvited is not the origin of the haunting of Winward House, but rather why so few movies like this one were made in the United States during the old days.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment